The Man Who Transported a Ship From England to the Shores of Peru’s Lake Titicaca | Travel News

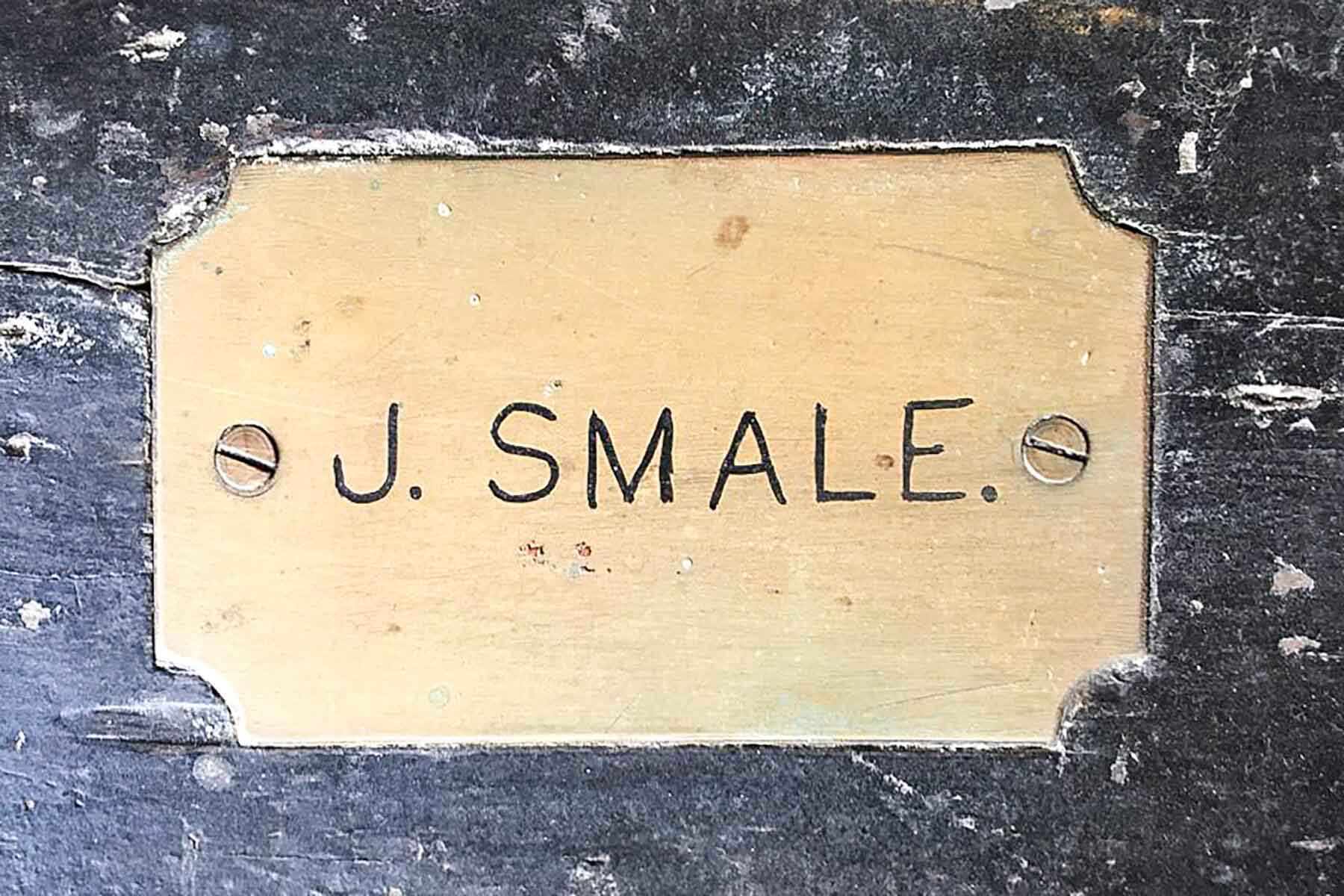

A young girl rummages through an old wooden chest with a lid marked with a simple plaque engraved: J. Smale. This chest once held tools belonging to Smale’s son, Bill, who was the girl’s great-great-uncle. One day, she would retrace Bill’s journey from the UK to Lake Titicaca, though his adventure was quite different as he was transporting a 2,000-ton steamship. That girl, Anna, grew up to share her great-great-uncle’s adventurous spirit.

Anna once told me, “When my parents spoke about Uncle Bill, I never imagined that I’d be traveling through South America myself, trying to find his ship on Lake Titicaca.”

We truly understood the scale of Titicaca and Bill’s feat when we visited the lake and sought out Uncle Bill’s ship.

Bill worked for Earle’s Shipbuilding in Hull, England, and was commissioned by the Peruvian Corporation to build a vessel for the world’s highest navigable lake. The completed S.S. Ollanta was dismantled, shipped across oceans to Mollendo, then transported by train to Puno. Bill traveled with the cargo and, upon arrival, quickly enlisted locals to build a slipway for the Ollanta.

As one of Britain’s top engineers in the early 20th century, Bill and the local crew reassembled the steamer swiftly, even before the rest of the team from England arrived. On November 18, 1931, the S.S. Ollanta was launched on Lake Titicaca. Earlier that year, the Prince of Wales also visited Puno.

The Ollanta had 66 first-class and 20 second-class cabins, and it’s possible that this was the ship Che Guevara referred to in 1952 when he described a “boat designed in England and built here; its opulence clashed with the region’s general poverty.”

Anna and I arrived in Puno from the same direction as Guevara, but in a comfortable bus from Bolivia rather than on a truck in freezing conditions.

“Most people probably don’t head straight for the docks when they get to Puno,” Anna said. “I was eager to see if the Ollanta was still here. Unfortunately, no one at the nearby craft market knew of it, or maybe they just didn’t understand what we were looking for.”

We walked along the quay, venturing into an area we weren’t sure we were allowed to enter.

“That turned out to be the right decision,” Anna recalls. “There, along the quay, was the ship Uncle Bill had built nearly 100 years ago.”

The S.S. Ollanta floated majestically next to an old corrugated-roof warehouse, its sleek black hull topped with shining white upper decks. Anna admired the ship her ancestor had built, though no one was around to let us board or get close. However, there were other old steamers at the docks.

Anna showed me the Yavari, another ship built in London in the same “knock down” method as the Ollanta. Constructed in 1862, it was deconstructed, shipped across oceans, and brought inland to Lake Titicaca without a rail connection. Each of its 2,766 pieces had to weigh less than 400 pounds for mule transport. Like the Ollanta, the Yavari was reassembled in Puno and launched in 1870.

The reed islands near the grand old steamers are as timeless now as they were when Bill Smale added his metal craft to the lake. Near the dock, tour boats depart for these islands, taking visitors to the Uros and Taquile villages, where reeds are used to build floating platforms and houses.

Earle’s Shipyard in Hull has been replaced by modern warehouses, but an old warehouse from Yavari’s builders, the Thames Ironworks shipyard, still stands in East London, now surrounded by high-rise apartments. Thanks to dedicated volunteers and specialists, both the Ollanta and Yavari are in much better condition than their original construction sites.

Meriel Larken, who mistakenly thought Yavari was built in her great-grandfather’s shipyard, traveled from the UK to Puno in 1982 to purchase the deteriorating ship from a Peruvian admiral. Contrary to expectations, the 120-year-old hull was in surprisingly good shape. It took Larken and a team of volunteers many years to restore the ship, and today, exploring its cabins, you can easily imagine the old engines once powered by llama dung.

There are hopes for Yavari to become a museum, but as of 2024, a new benefactor or management team is being sought to secure its future. If you visit the docks, you might also see the Yapura, Yavari’s sister ship, which belongs to the Peruvian government and was recently used as a coastguard vessel.

Although we saw Uncle Bill’s ship, Anna was still curious: did her ancestor meet the Prince of Wales?

After sifting through archives, I found that Bill left for South America on December 23, 1930, and took about a month to sail from Liverpool to Mollendo. The Prince of Wales arrived in Callao, Peru, in February 1931 and visited Lake Titicaca around the same time Bill would have been there. However, Bill is not mentioned in any reports, leaving this question unresolved.

“I’m sure the prince would have been honored to meet Bill,” Anna told me.

Further searching revealed an old document: a November 1932 manifest of passengers arriving in New York on the SS Santa Maria. Listed among those who boarded in Mollendo in October of that year was “William Smale,” aged 33, returning to England.

Anna followed in Bill’s footsteps, traveling through Peru and sharing his adventurous spirit. She journeyed through Ecuador, the Caribbean, and, like her great-great-uncle, returned home via New York.