Explore Quito: Top Attractions and Experiences | Travel News

Quito receives its official name, San Francisco del Quito, as a cultural treasure alongside UNESCO World Heritage status. People tend to overlook Quito when they plan their South American trips because they focus on the Amazon, Machu Picchu, and the Galapagos Islands, yet Quito stands out with its historical richness, cultural diversity, and adventurous opportunities that make it essential for any Ecuadorian travel plan. The city of Quito offers twenty essential attractions, which include its colonial buildings, stunning observation points, and nearby natural treasures.

1. Admire the City from Parque Itchimbía

The peak of Parque Itchimbía offers visitors an opportunity to see Quito from above, as the city unfolds through the valley while Pichincha Volcano creates a stunning backdrop. The location sits at an elevation of 2,850 meters above sea level, which makes it an excellent spot for taking photos and finding your way around the city.

2. Explore Plaza Grande – Quito’s Historic Heart

The plaza functions as the main square of the city while serving as the central historic district of Quito.

Visit Plaza Grande, also known as Independence Square, surrounded by:

- The Presidential Palace

- The Metropolitan Cathedral

- The Archbishop’s Palace

The location displays historical life through its monuments, which commemorate Ecuador's independence and its colonial past.

3. Take a Walking Tour of Quito’s Old Town

- Latin America houses its biggest historic center, which you can explore through a walking tour to see its remarkable developments.

- Spanish, Italian, Moorish, and indigenous art fused in the Baroque School of Quito.

- La Compañía de Jesús Church displays stunning gold leaf decorations.

- The area contains lively streets that host local merchants and traditional food markets.

4. Visit Catedral Metropolitana de Quito

One of Ecuador’s most iconic landmarks, the Quito Cathedral, built in 1535, houses priceless artworks, a museum, and a treasury.

5. Stroll Through La Ronda

Experience Quito’s traditional charm along La Ronda Street with:

- Cafes, bars, and restaurants

- Artisan workshops

- Vibrant nightlife

6. Learn Traditional Crafts at Esquela Taller Quito

The students and artisans work together to protect historical crafts through woodworking, embroidery, and gold-leaf techniques, which they use to restore Quito's colonial buildings.

7. Stand at the Equator – Mitad del Mundo

Visit Mitad del Mundo, where the French measured the equator in the 18th century, and take memorable photos at the 30-meter monument.

8. Walk the Equator Line at Museo Intiñan

The Museo de Sitio Intiñan, near the location, presents visitors with interactive displays about equatorial phenomena through entertaining water rotation and gravity effect experiments.

9. Ride the Teleférico Cable Car

Ascend to 4,100 meters for sweeping city views, and hike to Rucu Pichincha summit for stunning volcanic scenery.

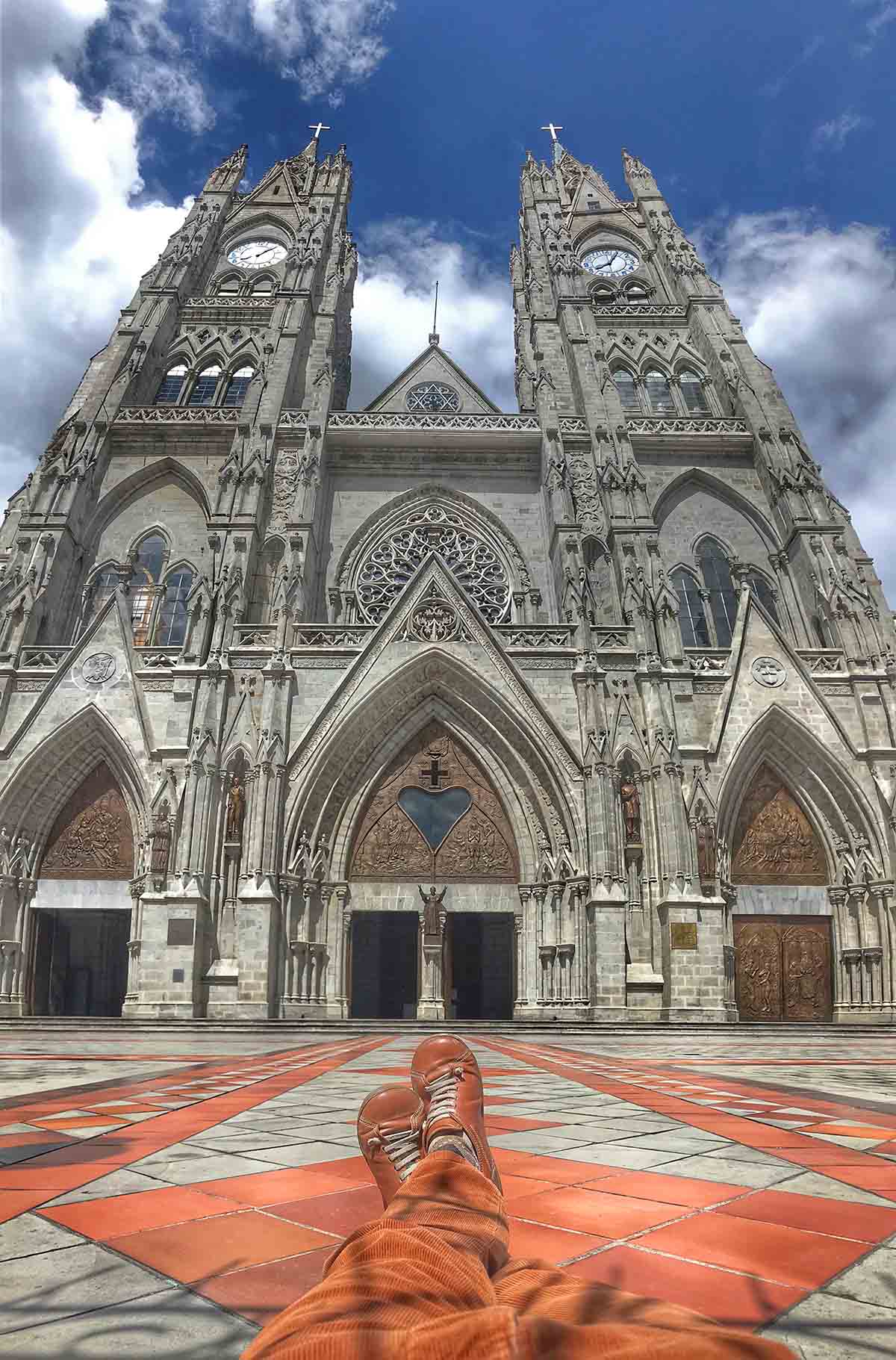

10. Visit Basílica del Voto Nacional

Visitors can reach the highest point of this neo-Gothic basilica to see Ecuadorian animal-inspired gargoyles while enjoying breathtaking views of Quito from above.

11. Enjoy a Trolley Tour of Quito

Travelers who want an easy method to explore Quito's slopes should choose the trolley tour, which provides a simple sightseeing option for people seeking a relaxed introduction to the city.

12. Day Trip to Antisana Volcano

The Antisana Ecological Reserve spans 5,700 meters and offers visitors the chance to see condors, Andean gulls, and to explore the distinctive páramo ecosystem.

13. Discover Mindo Cloud Forest

The Mindo Valley offers a full day of exploration, which includes exotic birds, orchids, butterflies, and adventure activities such as tubing, hiking, and ziplining.

14. Explore Otavalo Market

Otavalo serves as a center for indigenous textile production and handicrafts, and also offers a variety of unusual food items. The location is an ideal spot to buy souvenirs and experience local traditions.

Key Points: More Experiences to Enjoy

- Pichincha Volcano provides two main activities for visitors through its cable car system and hiking routes.

- The Quilotoa Lake offers visitors the chance to explore its scenic crater lake through hiking trails and kayaking experiences.

- The town of Baños de Agua Santa provides visitors with hot springs, waterfalls, and extreme sports activities.

- The Museo Guayasamín presents visitors with Ecuadorian artistic collections alongside historical artifacts from the nation, according to Things to Do in Quito.

Quito stands as more than a mere transit point because it represents a city that unites historical elements with cultural richness and adventurous possibilities. Visitors will create lasting memories through their exploration of colonial streets, hikes up volcanoes, and cloud forests.

Our 6-Day Quito City Tour and Jewel of the Andes Tour offer full itineraries and guided tours which provide a complete Ecuadorian adventure.