First map of vegetation across Antarctica reveals a battle for the continent’s changing landscape | Travel News

A tiny seed finds itself lodged between loose gravel and coarse sand, surrounded by a desolate landscape. The only thing in sight is a towering 20-meter wall of ice. The environment is harsh, with cold temperatures and challenging survival conditions. In winter, darkness persists even during the day, and in summer, the sun relentlessly bakes the ground, leaving it dry and hard for 24 hours straight.

This seed was left behind years ago by tourists visiting Antarctica, the last untouched wilderness on Earth.

The climate is changing, and as temperatures rise, glaciers are melting. The meltwater gives the seed a chance to grow. Antarctica is experiencing some of the fastest climate changes in the world. The melting ice could potentially raise sea levels by up to 5 meters. As the ice retreats, it exposes barren land. By the end of this century, a landmass equivalent to the size of a small country might emerge from beneath the ice.

Newly exposed land in Antarctica is quickly colonized by pioneer organisms. The first to appear are algae and cyanobacteria, tiny organisms small enough to fit between grains of sand. These algae, sheltered from the sun’s harsh rays, stick sand particles together as they grow and die, creating a surface for other organisms to take root.

Next come lichens and mosses. Though only a few centimeters tall, they tower over other life forms on Antarctica’s shores. Once they establish themselves, larger organisms may follow, eventually allowing plants to take hold. If a seed finds a soft, moist cushion of moss, it can thrive and grow.

Only two plant species are native to Antarctica, both of which spread their seeds through the wind. This makes them independent of animals and insects for pollination or seed dispersal. The wind carries their seeds to new patches of soil. All these plants need is a bit of moss or lichen to anchor themselves, preventing them from being blown away into the icy desert.

However, this natural progression of plant life has been disrupted as the climate changes, making the environment more habitable. Over 100 plant species have already invaded Antarctica. These newcomers are thriving. For example, Poa annua, a common lawn grass, has spread rapidly across the sub-Antarctic Islands from South Georgia to Livingston Island and is now advancing towards the Antarctic Peninsula.

Researchers are now exploring the potential for new plant species to flourish in Antarctic soils. What will Antarctica look like in 100 years? Could it resemble the green tundra landscapes of the Arctic?

A new map

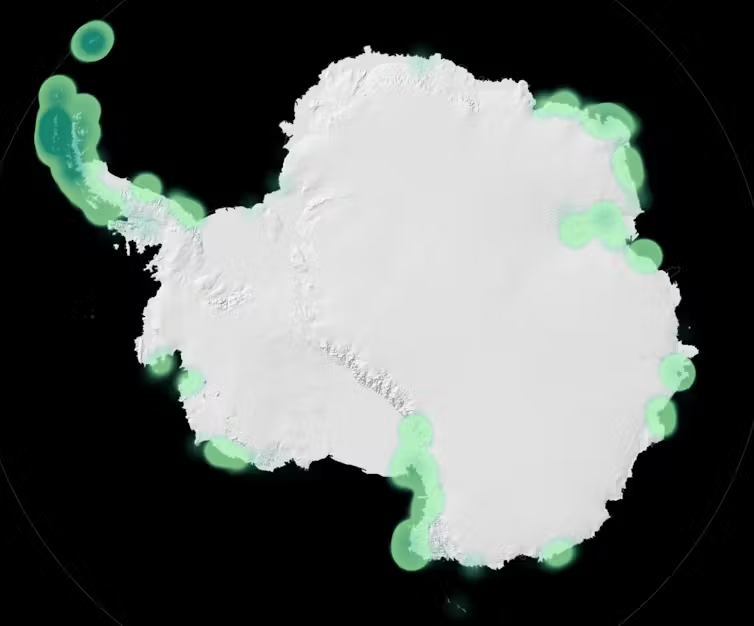

I’m part of a team of scientists who have recently used satellite data combined with field measurements to create the first map of green vegetation across the entire Antarctic continent.

We identified 44.2 km² of vegetation, mostly located on the Antarctic Peninsula and nearby offshore islands. This vegetation covers just 0.12% of Antarctica’s total ice-free area, underscoring that Antarctica is still largely dominated by snow and ice. For now.

Preserving the unspoiled Antarctic environment is crucial not only for its intrinsic value but also for its importance to humanity. The immense ice masses on the continent drive climate and weather patterns worldwide. Their disappearance would fundamentally alter the planet.

My colleague, Charlotte Walshaw from the University of Edinburgh, led the recent research on mapping vegetation in Antarctica. She emphasizes that these new maps provide crucial information at a scale previously unattainable. “We can use these maps,” she told me, “to closely monitor any large-scale changes in vegetation distribution patterns.”

Vegetation in Antarctica faces the harshest conditions on Earth. Only the most resilient organisms can survive there, and with climate change, their future remains uncertain. Now that we know where to find these plants, we can implement more precise conservation measures to protect them.